Taking Advantage of Payor Contracts: Pitfalls of Hospital Pass-Through Billing Arrangements

By Richard S. Cooper, McDonald Hopkins, LLC

By Elizabeth A. Sullivan, McDonald Hopkins, LLC

By Emily A. Johnson, McDonald Hopkins, LLC

By Donna M. Beasley, Huron Consulting Group

Original Publish Date: August 7, 2018

There are numerous new laboratory referral arrangements that involve billing which may implicate several laws at both the Federal and State level. Due to reduced reimbursements and narrower payor networks, these arrangements on the surface may seem advantageous and attractive as a means to increase revenues and align new clients. However, the health insurers as payors of pass-through laboratory claims are now recognizing and making attempts to stop the flow of these potentially fraudulent and lucrative schemes through lawsuits and tougher contracting.

1. What is Hospital Pass-Through Billing?

Pass-through billing arrangements are commonly identified basically where laboratory testing claims are billed by an entity different than the one that performed the service. Pass-through billing, sometimes known as account billing or client billing, is a billing model that has been around for years. The arrangement is essentially a purchased service agreement pursuant to which a provider contracts for the provision of laboratory services. The provider typically purchases laboratory services at a discount, marks up the price, and rebills the purchased services to patients and payors. In some instances, this is permissible as a reference laboratory arrangement, but in others, payor policies or federal or state laws may prohibit the practice depending on the type of provider.

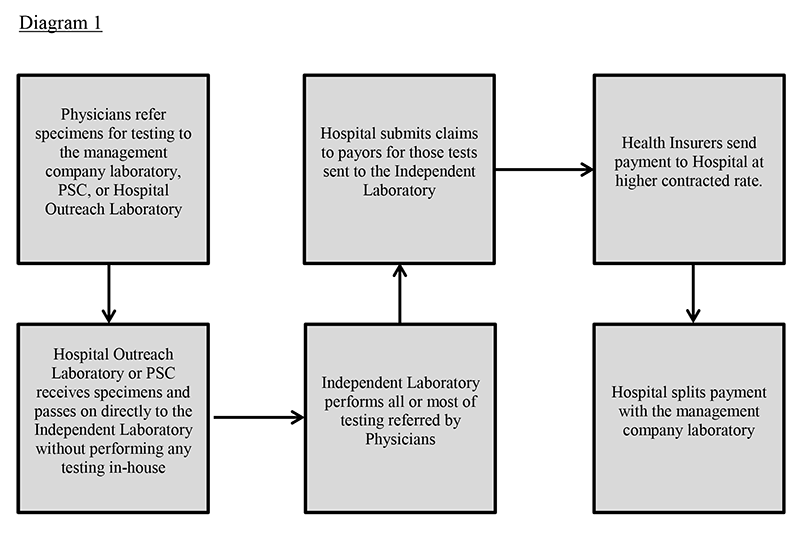

In recent years, a new form of pass-through billing has emerged termed by management companies as hospital laboratories. These arrangements often appear to target small, rural hospitals or hospitals which may be in need of capital, and typically only apply to services reimbursable by commercial payors. In a typical hospital pass-through billing arrangement, management companies affiliated with independent reference laboratories, or a laboratory itself will enter into an agreement with a hospital pursuant to which their associated client base is permitted to refer outreach testing to the hospital outreach laboratory. The hospital then bills non-governmental payors as an in-network provider. See Diagram 1 below. The independent reference laboratories in question may be out-of-network, which is more typical, but may be in-network as well. Regardless of their status, their claims have less favorable reimbursement than a hospital payor contract. The purpose of the arrangement with a hospital, is to take advantage of the hospital’s payor agreements, which yield a higher reimbursement, and the hospital benefits from the opportunity to increase their laboratory revenue and client market share. While this sounds advantageous to both parties involved, a problem arises when the laboratory testing is never performed by the hospital laboratory and is instead solely performed by the management company’s related independent reference laboratory.

*Note: The arrangement may be set up with the specimens going directly to the reference laboratory and only reports are sent to the hospital from which claims are submitted. There are multiple permutations of the hospital model, each with different compliance considerations.

At face value, this may appear to be an acceptable reference laboratory arrangement because a hospital is permitted to use reference laboratories for patient services and bill for the services under certain circumstances. However, in this case, payors take issue with paying a hospital for a test they did not perform at a higher contracted rate than the payor would have paid for the same test had the performing independent laboratory billed for the test themselves directly to the payor. This scheme may also increase the patient’s responsibility as well due to the more inflated pricing, which is solely for the financial gain of the management companies. Additionally, a larger, nationwide network of referring physicians to provide testing specimens is seen as desirable to fully utilize the capacity of laboratories and further increase testing volumes and laboratory revenues. However, a problem occurs when the physicians are submitting specimens in exchange for a portion of the reimbursement. This can lead to overutilization and ordering of medically unnecessary laboratory tests, and can constitute an illegal kickback or violation of the physician self-referral law, more commonly known as the Stark Law. Furthermore, the requests for laboratory testing services are often unlawful inducements that prey upon financially strained rural hospitals. These hospital laboratories are actually used as fronts to conceal the identity of the management company laboratories that actually perform the testing, especially if the CLIA number of the performing laboratory is not accurately depicted on the claim. Another strategy is for the management companies to actually help set-up the laboratory outreach programs in mostly rural hospitals for the sole purpose of the pass-through billing arrangement to take place. Finally, in some variations of these problematic arrangements, the hospital laboratory only accessions the specimens and then refers the specimen to the laboratory for testing. In this variation, the billing is not the only issue that is questionable. Arrangements where the management company helps the hospital set up a laboratory for the purpose of receiving and processing the specimens and the hospital submits the claim to the payor for reimbursement are seriously flawed. These arrangements are sometimes seen in toxicology, pain management, molecular diagnostic, and genetic testing. Once the hospital receives payment from the insurer, the hospital then splits the revenue according to an agreement with the management company/laboratory, which is also fraudulent.

The pass-through arrangement is often confusing for many hospitals and for that reason, they may not even realize they are being deceived. Hospitals are used to such arrangements with the national reference laboratories, but there are significant differences in these purchased service agreements that are fraudulent. The large national reference laboratories often have patient service centers (PSCs) in locations convenient to their physician clients and near hospitals. The payors actually often prefer a large number of PSCs to be considered in-network or exclusive. These large reference laboratories may even contract with the hospitals to do their STAT testing locally onsite at the hospital laboratory location with the understanding that other more esoteric testing be sent on to their reference laboratory. There are several differences in this type of scenario versus the hospital pass-through arrangements in question:

- When actually performing the test, the national independent laboratories will have their CLIA number printed on the report to the provider. In the October 20, 2017 edition of The Dark Report, it was noted that in the fraudulent cases of pass-through arrangements, the hospital laboratories include their own CLIA number on reports even if they are not the performing laboratory.

- As further discussed below, for a hospital laboratory to bill Medicare, they must perform at least 70% of all testing onsite. Under the Shell Lab Rule, which applies to Medicare testing, a hospital laboratory can refer to another laboratory and is permitted to bill for the referred work as long as no more than 30% of the tests for which the hospital laboratory receives orders during the year are performed by an outside laboratory. This should be a significant deterrent for a pass-through arrangement where the hospital laboratory passes on the specimen to a reference laboratory and the hospital laboratory performs no in-house testing and is only responsible billing the claim.

- The respectable arrangements do not ever split the revenue received as payment by the hospital. The hospital laboratory pays the independent laboratory fair market value for the testing performed, and such payment must exceed the cost for the laboratory to perform the test.

2. Regulatory Implications of Hospital Pass-Through Billing Arrangements?

There are many compliance concerns associated with hospital pass-through billing arrangements, including federal, state, and payor contract concerns. In addition to the various legal issues, these arrangements are clearly starting to attract the attention of state and federal regulators and private and commercial payors. This is largely due to the fact that under these arrangements, small, rural hospitals suddenly receive samples from patients all over the country with no nexus to the hospital, and the hospital’s overall revenues increase dramatically. Whenever there is such a drastic change, the arrangement will likely be scrutinized.

- Federal Fraud and Abuse Concerns

- Anti-Kickback

The federal Anti-Kickback Statute (“AKS”) prohibits payment, receipt, offering or solicitation of remuneration in exchange for the referral of services or items reimbursed by the Medicare or Medicaid programs. 42 U.S.C. § 1320a-7b. Hospital pass-through billing arrangements can implicate the AKS in a number of ways. First, the revenue split between the hospital and the performing laboratory or laboratory management company can be considered an inducement in exchange for receipt of the referral by the management company/laboratory. In other words, the hospital is paying the laboratory or management company for referring the specimen to the hospital so that the hospital can bill for laboratory services it did not perform. Second, any remuneration offered to the ordering providers to induce them to refer the testing to the laboratory in question would be considered a kickback or Stark violation in violation of federal law. This is why these arrangements typically exclude services reimbursable by a government payor (i.e., Medicare, Medicaid, Tricare, CHAMPUS, and Medicare Advantage). However, many states have similar laws applicable to all payor categories. - Stark

The federal physician self-referral law, commonly known as the Stark Law, prohibits a physician from making a referral for certain designated health services reimbursable by Medicare or Medicaid to an entity with which the physician has a financial relationship. 42 U.S.C. §1395nn. A hospital pass-through arrangement could implicate the Stark Law if it includes referrals by a physician to a laboratory that will share a portion of the revenue received for performing the laboratory services with the referring physician. Again, this is why hospital arrangements typically exclude services reimbursable by a government payor. - False Claims Act

Under the federal False Claims Act (“FCA”), a provider may be liable if he or she (1) knowingly presents (or causes to be presented) a false or fraudulent claim for payment; (2) knowingly makes, uses, or causes to be made or used, a false record or statement material to a false or fraudulent claim; (3) conspires with others to commit a violation of the FCA (4) knowingly makes, uses, or causes to be made or used, a false record or statement to conceal, avoid, or decrease an obligation to pay money or transmit property to the Federal Government. False claims are subject to recoupment and can create both civil and criminal liability for the billing provider. The FCA generally only applies to claims submitted to a federal program for reimbursement. However, many states have their own equivalent of the FCA, which would false claims from being submitted to private payors as well.

Depending on the terms of the applicable payor contract as well as applicable state law, the hospital may be contractually or legally obligated to only bill for services it performs. Therefore, if the hospital bills for services performed by another laboratory, the hospital could be breaching its payor contracts. Any claims submitted in violation of the payor contract or state law could be considered false claims under applicable state law. In addition, claims submitted to a payor for services resulting from a kickback, such as remuneration provided to the ordering provider in exchange for referring specimens to a particular laboratory, would be considered false claims subject to recoupment. Finally, billing for medically unnecessary services or upcoding services to achieve higher reimbursement would also be considered false claims. For these reasons, it is recommended that the terms of the applicable payor contracts and state law be carefully considered prior to entering a hospital pass-through arrangement. - Medicare Reference Laboratory Exceptions

The Medicare reference laboratory exceptions impose billing limitations on reference laboratory arrangements by prohibiting a referring laboratory from billing under the Clinical Laboratory Fee Schedule for diagnostic tests performed by a reference laboratory unless the following criteria are satisfied: (a) the referring laboratory is located in (or is part of) a rural hospital; (b) the referring laboratory and the reference laboratory are under some form of common ownership; or (c) the referring laboratory does not refer more than 30% of its clinical laboratory tests out to a reference laboratory during the year (not including referrals under the common ownership exception).

Hospital pass-through billing schemes are often marketed to hospitals by management companies or independent laboratories under the rural hospital exception. Specifically, the hospital is told that the arrangement is permissible because the hospital is located in a rural area and that the hospital is therefore permitted to refer testing to another laboratory for performance due to the fact that the other laboratory is more qualified and has more resources to perform the testing. This is the exception that is typically relied upon if the hospital pass-through billing arrangement includes testing reimbursable by government payors. However, although the arrangement appears to satisfy the exception on its face, the fact that there is usually no nexus between the hospital and the patient for whom testing is performed calls the arrangement into question.

The third exception, commonly known as the Shell Lab Rule, prevents hospitals from entering into reference laboratory arrangements with outside laboratories pursuant to which the outside laboratory performs the testing services and the hospital submits the claim to the applicable payor if the total test volume referred exceeds 30% of the total referrals received during the year. One purpose of this limitation is to prevent providers from shopping for the most favorable reimbursement rate. If a large number of specimens are referred, this 30% limit may be eclipsed. Even if the Shell Lab Rule can be satisfied and the test volume referred is less than 30% of the total referrals received in a given year, the arrangement must still be structured to comply with applicable Stark Law exceptions or AKS safe harbors if any remuneration is exchanged between the hospital, the reference laboratory, or the ordering physician.

- Anti-Kickback

- State and Payor Issues

In light of the significant federal fraud and abuse concerns regarding hospital arrangements, such arrangements are often proposed only for laboratory services reimbursable by commercial payors. However, as explained below, eliminating services reimbursed by a government payor is not enough to mitigate the risks associated with these arrangements, and there are still significant state and payor issues to consider. For example, as noted above, most states have Stark, AKS, and FCA equivalent laws that would apply.- Direct Bill and Anti-markup Laws

Many states have statutory restrictions on pass-through billing and markup, although some of the provisions only relate to professional component services and not technical component. There are four categories of state regulations: direct billing, anti-markup, disclosure, and unregulated. In direct billing states, laboratories (and, in some states, other third parties) are required to bill payors directly for the services they perform. In anti-markup states, a provider that purchases laboratory services is prohibited from marking up the cost of such services above the amount he or she paid to the laboratory. In disclosure states, the purchaser must disclose the name of the selling laboratory, the amount paid for the laboratory service, and the amount of any markup. In unregulated states, there is no apparent statutory prohibition on markup or billing for purchased services.

It is worth noting that in most states, hospitals are specifically excepted from direct billing and anti-markup regulations. This is another angle through which hospital pass-through arrangements are marketed. As stated above, however, regulators may take issue with the fact that there is usually no nexus between the hospital and the patient for whom testing is performed as the patients are often from geographically remote locations. - Payor Concerns

More and more payors are restricting the ability of participating providers to bill for purchased services. Where it is restricted, payors will limit or deny payment for services when billed by the purchaser of the services as opposed to the performing laboratory. Furthermore, many payor agreements have anti-assignment language which would prohibit a provider from referring services to another provider for performance. The terms of applicable payor agreements should be consulted before entering into a pass-through billing arrangement.

In addition, when payors contract with hospitals, they take into consideration the hospital’s inpatient, outpatient, and outreach work for purposes of establishing the patient base and contract terms. Payors do not believe that the agreements cover the types of “patients” that arise from a hospital arrangement.

Payors regularly monitor provider reimbursement trends. When they discover that a hospital’s laboratory claims has spiked, payors take notice and investigate the cause of the spike. The increased claims become particularly concerning when a payor reimburses a high volume of claims in a short period of time for a hospital located in a rural area where there could not possible be such a demand for laboratory services. As a result of these arrangements, payors are losing significant money. As a result, there is increasing enforcement by payors to recoup amounts reimbursed under a hospital arrangement under theories of breach of contract, fraud, civil conspiracy, negligent misrepresentation, and unjust enrichment.

- Direct Bill and Anti-markup Laws

3. Recoupment Exposure

The billing hospital will be directly liable for any recoupment claim successfully brought by a payor related to the billed tests in question since it is the hospital that billed the services and has a contract with the payor. This means that the hospital, and not the management company/laboratory, will be the subject of any recoupment action based upon theories such as lack of medical necessity – an increasingly common basis for recoupment actions

4. Noteworthy Lawsuits and Claims.

- Blue Cross Blue Shield of Mississippi v. Sharkey-Issaquena Community Hospital et al.

On May 4, 2017, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Mississippi (“BCBS of MS”) filed a lawsuit against Sharkey-Issaquena Community Hospital (“Sharkey-Issaquena”) and four off-site laboratories which BCBS of MS alleged performed laboratory services for which Sharkey-Issaquena wrongfully submitted claims. Specifically, BCBS of MS alleged that, beginning in February 2017, Sharkey-Issaquena submitted claims to BCBS of MS for reimbursement for laboratory services that were not ordered by a licensed physician or other licensed health professional with privileges at Sharkey-Issaquena and/or were not performed at Sharkey-Issaquena. BCBS of MS stated that the defendants utilized Sharkey-Issaquena “as a vehicle to disguise fraudulent claims, which misrepresented that laboratory testing services were performed by and at the Hospital, when in truth, all testing services were performed by independent, non-network laboratories.” Blue Cross & Blue Shield of Mississippi v. Sharkey-Issaquena Community Hospital, et. al., 2017 WL6375954 (S.D. Miss. 2017), citing BCBS of MS’s responsive memorandum at page 2. The laboratories “completed, or caused to be completed, the laboratory tests at issue for patients from around the country who had no contact at all with [Sharkey-Issaquena] or its physicians” and Sharkey-Issaquena then “fraudulently submitted claims to Blue Cross, misrepresenting that the tests had been performed at the Hospital, by the Hospital, and for the Hospital’s patients.” Id.

The complaint filed by BCBS of MS includes claims for breach of contract, fraud, civil conspiracy, negligent misrepresentation, and unjust enrichment. BCBS of MS alleges that Sharkey-Issaquena, a small, twenty-nine (29) bed rural hospital, submitted nearly $34 million in outreach laboratory test claims in only 120 days. BCBS of MS seeks repayment of $9.8 million dollars and forgiveness of the nearly $24 million worth of claims that remain unpaid to Sharkey-Issaquena. - Aetna, Inc. v. People’s Choice Hospital, LLC.

On September 29, 2017, Aetna filed a lawsuit against People’s Choice Hospital (formerly known as Newman Memorial Hospital) (“PCH”), a twenty-five (25) bed critical access hospital in Shattuck, Oklahoma. Aetna alleged that PCH fraudulently billed for laboratory tests performed off-site for patients from all over the United States and who were not part of Aetna’s network. The defendants include the hospital, a management company, eight (8) clinical laboratories or laboratory management companies, two (2) physicians, and two (2) individuals. According to the complaint, the clinical laboratories performed the testing and PCH merely submitted the claims to Aetna. Specifically, the lawsuit alleges that the management company and clinical laboratory defendants had unfettered control over PCH and caused PCH to purchase laboratory equipment and hire employees for a laboratory at PCH that was never actually used. PCH was persuaded to enter into this arrangement due to its financial hardship. The other defendants promised PCH that entering into the arrangement would alleviate the hospital’s debt.

As soon as the management arrangement took effect, PCH submitted more than 10,000 claims to Aetna for laboratory testing over a sixteen (16) month period and generated over $21 million (or $1.35 million per month) as a result. Prior to this arrangement, PCH billed on average seventy-two (72) laboratory claims per month for an average monthly reimbursement of $1,300. PCH was paid an average of $2,250 per claim for urine and blood toxicology testing it did not perform. The performing laboratories would have only received approximately $120 for the same testing had they billed Aetna directly.

Aetna seeks damages in the amount of $21 million, the entire amount that was billed as a result of the fraudulent arrangement. - Blue Cross Blue Shield of Georgia v. Chestatee Regional Hospital, et al.

On March 28, 2018, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Georgia (“BCBS of GA”) filed a lawsuit against Chestatee Regional Hospital (“Chestatee”), a forty-nine (49) bed hospital in rural Dahlonega, Georgia, alleging that since 2016, Chestatee billed BCBS of GA more than $174 million for laboratory tests that BCBS of GA did not agree to pay for. The lawsuit alleges that Chestatee billed for laboratory tests as if they had been performed at and by Chestatee but which were actually performed by Reliance Laboratory Testing, Inc. (“Reliance”). The claims submitted for reimbursement were primarily for toxicology testing.

According to the lawsuit, Chestatee was a struggling hospital on the brink of closure before it was acquired by Durall Capital Holdings (“Durall”) in August 2016. Durall is common player in suspect hospital pass-through billing arrangements. Durall also owns Reliance. As an independent clinical laboratory, Reliance yields on average $100 to $300 from BCBS of GA for a urine drug test. For the same test, Chestatee receives more than $1,400.

Almost as soon as the transaction closed, Chestatee began billing for toxicology laboratory services. Prior to its acquisition, Chestatee billed approximately thirty (30) urine drug tests per month. After its acquisition, that number rose to a shocking 4,800 urine drug tests per month. BCBS of GA alleges that the tests were performed by Reliance and simply billed by Chestatee to take advantage of its more favorable reimbursement rates. Chestatee then split the profits with Reliance. The lawsuit further alleges that Reliance paid referring providers kickbacks to induce them to refer laboratory specimens to Chestatee.

BCBS of GA is seeking repayment of the entire amount it paid to Chestatee in connection with this billing scheme. The lawsuit also makes mention of a similar billing arrangement in place at Putnam County Memorial Hospital (“Putnam”), a small, rural hospital in Unionville, Missouri. Putnam is alleged to have submitted $92 million for laboratory tests over a period of just a few months. The owner of Putnam is one of the named defendant’s in the Chestatee lawsuit. It would not be surprising if a similar lawsuit is filed against Putnam in the near future. - Sonoma West Medical Center (Anthem)

On January 9, 2018, Anthem sent a letter to Sonoma West Medical Center (“SWMC”), a thirty-seven (37) bed hospital located in Sebastopol, California, demanding repayment of $13.5 million that Anthem paid in connection with claims for toxicology testing. Anthem alleges that since April 2017, SWMC engaged in an improper billing scheme with Palm Drive Health Care District to defraud Anthem and its Blue Cross and Blue Shield affiliates. The letter stated that SWMC “appears to have conspired with several third parties to fabricate or misrepresent claims for toxicology testing services that were improperly billed to Anthem.” Specifically, providers from all around the United States refer specimens to Reliance. In turn, Reliance distributes the specimens to various laboratories, including SWMC, for screening. Reliance allegedly maintains a portion of the specimens for testing and passes on a portion of the specimens to SWMC for additional testing. The Anthem letter further states that SWMC then “bills Anthem for some or all of the testing performed – representing that it had performed the testing when, in fact, it had not.” Further, Anthem’s review of the claims shows that most of the samples for which [SWMC] billed Anthem were collected from patients with no nexus to SWMC whatsoever. Such patients did not receive treatment at SWMC nor were they treated by a physician associated with SWMC who ordered the laboratory services to be performed at SWMC.

Prior to engaging in this arrangement, SWMC had filed for bankruptcy twice and was about to close its doors for good. However, in April 2017, Durall approached SWMC and proposed that the hospital enter into a laboratory management agreement with Durall in exchange for a loan of $2.1 million to be used in part to purchase toxicology testing equipment for SWMC’s laboratory. Pursuant to the arrangement, SWMC would bill for testing performed by Reliance. The Anthem letter stated that the reimbursement rate for services wrongfully billed by SWMC were often ten (10) times or more the rate that Reliance would be paid had the services been billed directly by Reliance. SWMC received approximately $4,000 for each drug panel it billed. According to the letter, “From July to December 2017, SWMC received more than 24,000 screening panels” and since then, SWMC’s test volume has nearly doubled to 7,000-8,000 tests each month. The letter further explained that this type of billing arrangement violated California law, the AKS, the FCA, and could lead to SWMC’s civil liability under California law.

On February 23, 2018, SWMC and the Palm Drive Health Care District voted unanimously to reject Anthem’s claims and released a statement that SWMC performs “quality legal and morally correct work.” It is likely that Anthem will file a lawsuit against SWMC to recover the money that Anthem claims should not have been paid due to the fraudulent pass-through billing arrangement. - LifeBrite Hospital Group of Stokes LLC (Blue Cross Blue Shield of North Carolina)

Blue Cross Blue Shield of North Carolina (“BCBS of NC”) recently announced that effective as of August 21, 2018, LifeBrite Hospital Group of Stokes LLC (“LifeBrite”) will be removed from the BCBS of NC in-patient network. BCBS of NC alleges that LifeBrite engaged in a fraudulent scheme to enrich itself at the payor’s expense by billing for laboratory services that were not payable, were fraudulent, and were in violation of LifeBrite’s payor agreement with BCBS of NC. Specifically, BCBS of NC has alleged claims of fraudulent misrepresentation, negligent misrepresentation, breach of contract, breach of contract accompanied by a fraudulent act, and unfair and deceptive trade practices.

LifeBrite purchased the hospital in bankruptcy in December 2016 for $400,000. The hospital was previously owned by Pioneer Health Services. According to BCBS of NC, since February 2017, LifeBrite had a 25,000 percent increase in submission of lab tests. Previously, the hospital submitted claims for an average of 267 laboratory tests per month, and that number rose to 67,000 post closing. The majority of the tests were for urine drug screenings. Since August of 2017, the hospital had a 22,000 percent increase in monthly laboratory billing (from $37,400 to $8.5 million), for a total of $76 million over a nine (9) month period. In April 2018 alone, LifeBrite submitted 133,995 claims and billed for $16 million in reimbursements.

LifeBrite is in the middle of a similar dispute with Aetna Health of the Carolinas, Inc. Aetna accused LifeBrite of similar increases in urine drug test submissions and terminated its contract with LifeBrite. - Bay Area Regional Medical Center (Aetna)

On May 10, 2018, Aetna filed a lawsuit against Southwest Laboratories, ESA Toxicology, B.M. Medical Management Service LLC, Strategic Ancillary Services, LLC, Elite Ambulatory Surgery Centers, LLC, and two individuals. In its complaint, Aetna alleges that Bay Area Regional Medical Center (“BARMC”) agreed to kickbacks in exchange for allowing a Houston laboratory, ESA Toxicology, use BARMC’s payor contracts and that bribes were paid by ESA Toxicology and Southwest Laboratories to send urine, blood, and saliva specimens to the laboraotries. The doctors were allegedly paid bonuses or monthly dividends as high as $30,000 a month in exchange for sending a high volume of specimens to the laboratories.

Aetna claims BARMC allowed the laboratories to use BARMC’s name when submitting claims, which increased the reimbursement provided by Aetna for the testing. Aetna claims the fraudulent billing arrangement amounted to $50 million in overpayments.

5. Structuring a Proper Outreach Reference Laboratory Arrangement

Though there are many regulatory issues to consider when structuring a hospital outreach laboratory, it is certainly possible to establish a legitimate outreach program that generates revenue for a hospital. First and foremost, the hospital must actually perform 70% of the testing that it is billing for. If this factor is not satisfied, it is critical that the hospital comply with all applicable Medicare reference laboratory exception and any other applicable state or commercial payor requirements for non-Medicare work. This distinguishes the arrangement from the hospital pass-through billing arrangements discussed above. Next, any remuneration exchanged among the hospital, the performing laboratory, the management company (if applicable), and the referring provider must be structured in a manner that satisfies applicable Stark Law exceptions (again, this only applies if doctor is receiving remuneration) and AKS safe harbors, as well as any state law equivalent. Also, applicable state law must be consulted to determine whether the hospital is even permitted to bill and markup the cost of services for services it does not personally perform. Finally, the terms of the hospital’s payor agreements must be carefully analyzed to determine whether such an arrangement is even permitted under the contract.

In order to compliantly bill for hospital outreach laboratory services and optimize the revenue management, laboratory specific consultants are recommended. This will help to ensure that claims are accurately submitted and AR oversight is maximized while monitoring that as the outreach program is operating at a high quality to include proper reporting. The arrangement should also be reviewed by an attorney well-versed in healthcare regulatory issues to verify that the arrangement complies with applicable federal and state laws and regulations, as well as with the terms of the hospital’s payor agreements.